Cod fishing has its history. Like everything else. Even a butterfly in Costa Rica has history, eventhough its life is as short as two days.

The inspiration for writing this is twofold: first of all, I like eating cod; second, I read morcels of cod fishing’s history in Fernand Braudel’s masterpiece “The Structures of Everyday Life: Civilisation and Capitalism, 15th – 18th Century”, and I liked it. So I got to write about cod, because I like eating it, and history, because I like reading it.

The topic is huge, so the piece is short. In this case being short enables the article to see the light of day.

Otherwise, it would remain in the depths of the box with unfulfilled tasks.

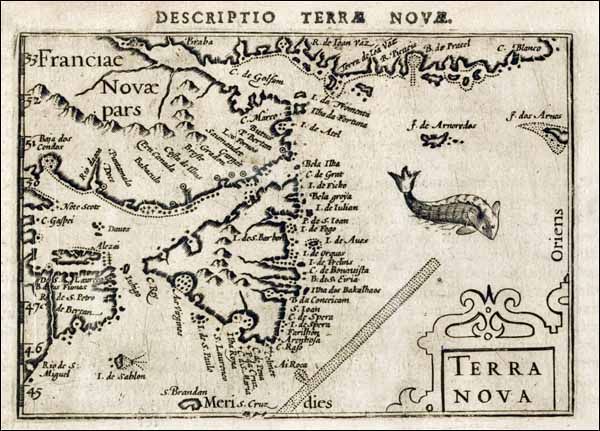

In shortening it, I had to limit the fishing area to Terra Nova, off the Northeastern Coast of Canada’a mainland.

But this will not limit the story to unfold.

The Northeastern territory of Canada, Newfoundland, was for almost 500 years since 1497 the area in the Atlantic where cod was fished in large quantities.

Until 1992, when the Canadian Government banned cod fishing in Newfoundland.

This decree ended more than 500 years of cod fishing in the area of Newfoundland.

…(the ban) put an estimated 30,000 people out of work and escalated the exodus of people from rural Newfoundland. It was the single largest layoff off of workers in Canadian history. Some social scientists say more than 70,000 people have left the bays, coves and outports of the province since. (2)

But how did it all start?

The name of the person who allegedly discovered Newfoundland is Giovanni Caboto. Born in Venice in 1450, Giovanni went to England and in 1496 he got the necessary sponsoring from King Henry VII and Italian financiers to go west and discover new lands.

He did so in 1497, when he landed on what is known today as Newfoundland.

In 1497 the English explorer John Cabot sailed through the waters off the coast of Newfoundland and was astounded at the incredible number of cod which surrounded his ship the Mathew. They had only to lower baskets into the ocean and let them fill with fish and retrieve a large catch. It was suspected that English fishermen may have already been fishing this area now known as the Grand Banks. Many other countries, such as France, Spain and Portugal, joined in the fishing banks for the summer seasons and established summer bases to salt and process the fish. (4)

Cabot’s ship was the “Matthew”, a caravel with 18 crew members. Today you can see its replica in Bristol, England.

So 500 years after the Vikings had landed on this land, Cabot did the same and brought in his journey back the good news to England and Europe.

Reports that Newfoundland and Labrador’s waters were rich in codfish were of interest to European governments for a variety of reasons at the turn of the 16th century. France, Portugal, and Italy all lacked sufficient supplies of protein for their populations, creating a demand for fish and meat imports on domestic markets. Cod was a good source of protein that preserved well and was easy to transport. Further, commercial fisheries were already an important part of the European economy and merchants could find buyers for new cod imports with relative ease by using existing trade networks. (6)

Sir Richard Whitbourne, who has spent thirty years of his life in Newfoundland, wrote in his “A Discourse and Discovery of Newfoundland” (1620):

“Although I well know, that it is an hard matter to perswade people to aduenture into strange Countries; especially to remain and settle themselues there, though the conditions thereof be neuer so beneficiall and aduantagious for them: yet I cannot be out of all hope, that when it shall bee taken into consideration, what infinite riches and aduantages other nations (and in partiuclar, the Spaniards and Portugals) haue gotten to themselues by their many Plantations, not onely in America, but also in Barbary, Guinnie, Binnie, and other places: And when it shall plainly appeare, by the following Discourse, that the Countrey shall plainly appeare, by the following Discourse, that the Countrey of New-found-land (as it is here truly described) is little inferior to any other for the commodities thereof; and lies, as it were, with open armes towards England, offering it selfe to be imbraced, and inhabited by vs: I cannot bee out of hope (I say) but that my Countreymen will bee induced, either by the thriuing examples of others, or by the strength of reason, to hearken, and put to their helping hands to that, which will in all likelihood yeeld them a plentifull reward of their labours.”

The transatlantic fishery further helped the European economy by creating jobs for workers directly and indirectly involved in the harvesting of fish. Alongside the thousands of people who travelled to Newfoundland and Labrador each year were the many more who manufactured nets, hooks, barrels, salt and other goods associated with the catching, processing, and packaging of fish. Other workers found employment with merchant firms selling cod to domestic and foreign markets. Alongside its economic benefits, the migratory cod fishery also became attractive to many European governments as a means of supplying skilled seamen to their navies and armadas. (6)

The French, Spanish and Portuguese fishermen tended to fish on the Grand Banks and other banks out to sea, where fish were always available. They salted their fish on board ship and it was not dried until brought to Europe. The English fishermen, however, concentrated on fishing inshore where the fish were only to be found at certain times of the year, during their migrations. These fishermen used small boats and returned to shore every day. They developed a system of light salting, washing and drying onshore which became very popular because the fish could remain edible for years. Many of their coastal sites gradually developed into settlements, notably St. John’s, now the provincial capital. (10)

The Northern Cod were so plentiful that until the late 50’s over 250,000 tons was caught on an annual basis. The Canadian fishing industry would traditionally fish just off the coast in smaller vessels using traditional methods such as jigging from a dory or small inshore gill nets. In the late 50’s the arrival of large factory ships from other countries hailed the first onslaught to the finely balanced renewable cod fishery. (4)

Scientists, policy makers, and fishermen say the commercial extinction of cod here began after World War II, when factory-sized trawlers, first from Europe and then from Canada, began vacuuming up the seas. As the massive ships took in well over a billion pounds of cod a year, rising global temperatures began melting Arctic ice, cooling the surrounding waters and severely stressing the thinning stocks, fisheries scientists in Newfoundland said. Other sources of food for cod, particularly a type of smelt called capelin, also began to decline sharply. (3)

The world’s largest freezing trawler by gross tonnage is the 144-metre-long Annelies Ilena ex Atlantic Dawn, presently alongside Killybegs harbour, having been detained in November 2013 by the Irish Navy and the Sea Fisheries Protection Agency for breach of regulations. She is able to process 350 tonnes of fish a day, can carry 3,000 tons of fuel, and store 7,000 tons of graded and frozen catch. She uses on board forklift trucks to aid discharging. (9)

The vessel sparked a political controversy after it was built in Norway and delivered to Ireland in 2000 for late skipper and fleet owner Kevin McHugh at a time when the European Commission was trying to reduce overall fleet sizes. (8)

With the arrival of these foreign fleets and the huge increase in their ability to net the fish, the annual catch, in 1968 increased to over 800,000 tons. At this level the cod were not able to renew their numbers and the available cod began to decline so that by 1975 the annual catch had declined to 300,000 tonnes. (4)

It was these floating fish factories owned by Canadian, Spanish and Portuguese corporations (plus other EU countries) that fished the northern cod to the brink of extinction before moving on to do the same with other species in South America and West Africa. (2)

The fishing technology had also taken another destructive leap in catch power by with deployment and use draggers. These ships dropped huge nets that were dragged along the bottom of the ocean which caught everything in its path and destroyed the underlying eco-system in the process. Fish, young fish, other sea life and the food source for the cod were all being destroyed in order to keep the catch rate on the rise. The entire eco-system was upset and destabilized. Much of the cod that was caught were spawning fish and hence the reproductive cycle was also disrupted. (4)

Ironically, the establishment of the 200-mile limit in 1977 by Canada did more to destroy the Newfoundland fishery than protect it. With the new limit the government encouraged, licensed and financed fisherman and fish companies to build bigger boats and enterprises to exploit the new fishing zones. A 400-year-old passive fishery became an active and aggressive hunting enterprise. They were encouraging overfishing.(2)

Where do we stand now?

There is still cod in the Atlantic. For example, off the coast of Maine, in the USA.

Also there is cod in the North Sea.

There is also some good news.

Whole Foods, a USA food market chain, announced in April 2012 that they would stop selling fish caught in a way that depletes its stock.

“Stewardship of the ocean is so important to our customers and to us,” said David Pilat, the global seafood buyer for Whole Foods. “We’re not necessarily here to tell fishermen how to fish, but on a species like Atlantic cod, we are out there actively saying, ‘For Whole Foods Market to buy your cod, the rating has to be favorable.’ ” (7)

Cod caught by trawlers in nets that drag nets across the ocean floor will no longer be bought and sold by Whole Foods.

A lot more needs to be done.

Sources

2. The day the fishery died. By Greg Locke. Herald, Arts and Life.

3. In Canada, cod remain scarce despite ban. By David Abel. Boston.com

4. Cod collapse. Canada History.

5. The international fishery of the 16th century. Newfoundland Heritage.

6. Origins of migratory fishery. Newfoundland Heritage.

7. A ban on some seafood has fishermen fuming. The New York Times.

8. Former Atlantic Dawn ship detained in Irish waters. The Irish Times.

9. Factory Ship. Wikipedia.

10. Cod fishing in Newfoundland. Wikipedia.